In this module, we will look at the relation between phonological processes and lexical variation in the sign language lexicon. A phonological process refers to an application of a certain constraint or rule on the phonological shape of the (underlying) input form in order to generate the output form (Quer et al., 2017). Phonological processes are found in all natural languages, spoken or signed. In spoken languages, a phonological process results in a systematic change that affects a sequence of sounds or a class of sounds. In sign languages, a phonological process affects one or more phonological parameters of the surface form of a sign. Below are some common phonological processes illustrated by examples in English and Hong Kong Sign Language.

In spoken languages, assimilation is a phonological process that alters the features of a sound segment (i.e., a consonant or a vowel) to make it more similar to another sound, typically a neighboring sound. Assimilation is very common, and it can occur between two words or within a word. In English, for example, the /t/ sound of best man may be pronounced as [p] in fast speech when it is followed by the bilabial nasal /m/ of man. /t/ and /p/ are voiceless stops and their only difference is the place of articulation: /t/ is alveolar (i.e., articulated at the alveolar ridge right behind the front teeth) whereas /p/ is bilabial (i.e., articulated by the upper and lower lips). /t/ is assimilated to [p] in anticipation of the following bilabial nasal /m/. This is an assimilation of the place of articulation. Another similar assimilation example is the word bank, in which the alveolar nasal /n/ becomes the velar nasal [ŋ] under the influence of the voiceless velar plosive /k/.

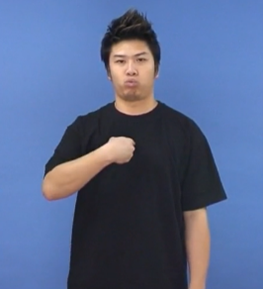

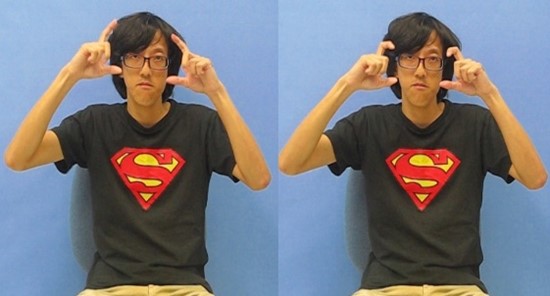

Assimilation is common in sign languages, too. It can affect one or more phonological parameters in a sign, and may occur across two signs or within a sign. In HKSL, the citation form of the first person single pronominal sign IX[=me] involves an extended index finger touching the chest of the signer:

In spontaneous discourse, this pronominal sign may assume the handshape of the following sign due to anticipatory assimilation.

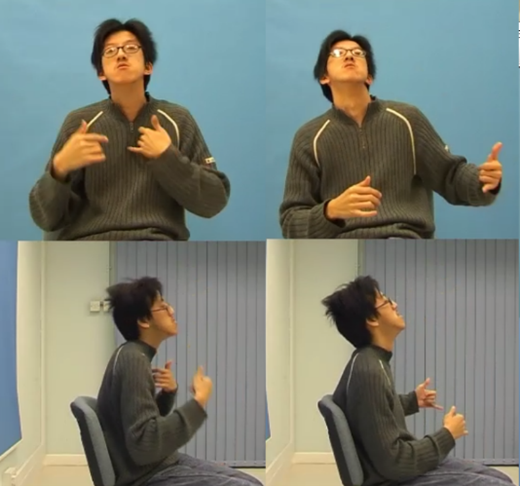

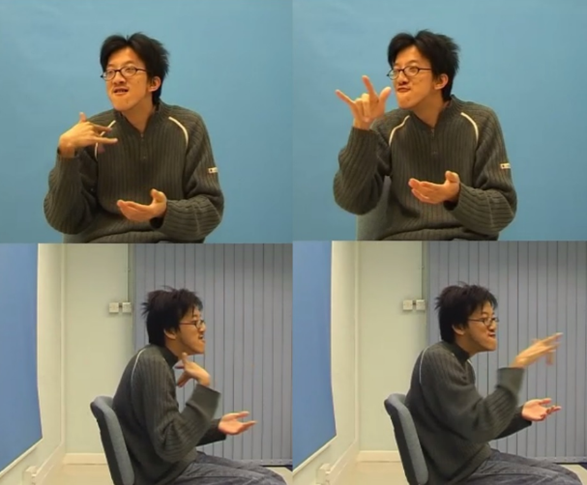

The two examples of HKSL below are extracted from a spontaneous conversation between two native signers. In these two examples, the first person pronoun assumes the handshape of the following sign (i.e., SIT and GUARD-AGAINST).

This kind of handshape assimilation of the first pronominal sign has previously been reported in other sign languages, too, e.g., ASL (Corina, 1990), Israeli Sign Language (Sandler, 1999).

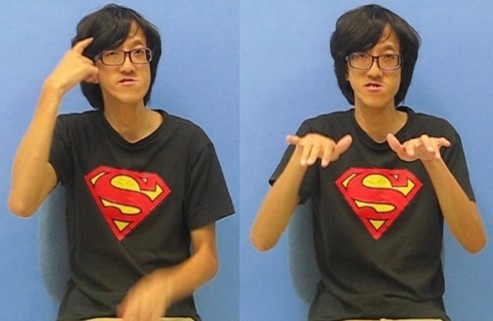

Assimilation may occur within a sign as well. In HKSL, the original form of CAMERA depicts the manual gesture of holding a camera and pressing the shutter button (CAMERA-1). Only the index of the dominant hand flexes at the non-base joint. In another derived variant of the same sign (CAMERA-2), the button-pressing action spreads to the other hand. This is an instance of movement assimilation.

Assimilation may occur within a compound. In HKSL, HABIT is a compound consisting of MIND and BREAK. HABIT-1 below shows the original compound without any assimilation. HABIT-2 is another variant with a handshape assimilation of MIND, due to the influence of the following sign BREAK.

Another common phonological process is deletion (also known as elision), which is broadly defined as the omission of one or more phonological segments. In spoken languages, what gets deleted can be a vowel, a consonant or a whole syllable in a word. In English, for example, family /fæ.mɪ.li/ consists of three syllables. The vowel in the second syllable may be deleted, resulting in [fæm.li]. Another example is him /hɪm/, in which the initial consonant is deleted by some speakers, i.e., [ɪm].

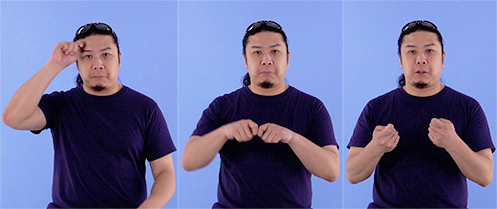

In HKSL, deletion can sometimes occur in two-handed signs. The two examples below show two of the several possible variants of ‘classmate’. CLASSMATE-1 is two-handed, while CLASSMATE-2 is similar to CLASSMATE-1 but one of the hands is deleted.

Deletion of a sign in a compound is fairly common in HKSL. The two signs below are two variants of ‘computer’. COMPUTER-1 is a compound consisting of BRAIN and TYPE (note: the Chinese word for ‘computer’ is a compound made up of ‘electrical’ and ‘brain’. The HK sign for ‘computer’ is partially based on this Chinese expression). COMPUTER-2 only retains the second sign of COMPUTER-1, with the first sign entirely deleted.

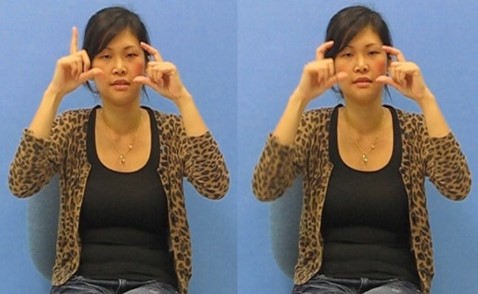

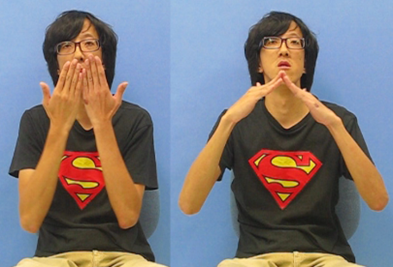

The third kind of phonological processes to be discussed here is metathesis. It occurs when two sounds or syllables switch places in a word. In English, ask /ɑsk/ is sometimes pronounced as [ɑks], in which the [s] and [k] sounds change their order of occurrence. In HKSL, the canonical way to sign DEAF requires the extended pinky to touch the ear and then the mouth. Under some circumstances, the order of the two contactual movements can swap. This kind of metathesis has been found in DEAF in ASL, too (e.g., Liddell & Johnson, 1989)

Another example of metathesis is SCHOOL in HKSL. The original sign (SCHOOL-1) is a compound consisting of STUDY^HOUSE (based on a direct translation of the corresponding Chinese word). Another variant of this sign (SCHOOL-2) reverses the order of the two signs.

Many of the HKSL examples discussed above (i.e., CAMERA-1 and CAMBER-2, CLASSMATE-1 and CLASSMATE-2, COMPUTER-1 and COMPUTER-2, SCHOOL-1 and SCHOOL-2) show that the phonological processes can generate new variants from the existing signs. These lexical variants are called phonological variants. In fact, a significant proportion of lexical variants in HKSL result from phonological processes. Not all lexical variants are phonological related, though. In HKSL, for example, apart from HABIT-1 and HABIT-2, another lexical variant (HABIT-3) is an entirely different sign. This is known as a separate variant. These phonological and separate variants can co-exist in the lexicon at the same time.

References:

- Corina, D. P. (1990). Handshape assimilations in hierarchical phonological representation. In C. Lucas (Ed.), Sign language research: Theoretical issues (pp. 27-49). Gallaudet University Press.

- Liddell, S. K., & Johnson, R. E. (1989). American Sign Language: The phonological base. Sign language studies, 64, 195-278.

- Quer, J., Cecchetto, C., Donati, C., Geraci, C., Kelepir, M., Pfau, R., & Steinbach, M. (2017). Signgram blueprint: A guide to sign language grammar writing. Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- Sandler, W. (1999). The medium and the message: Prosodic interpretation of linguistic content in Israeli Sign Language. Sign language & linguistics, 2(2),, 187-215.

![]()