As we mentioned in the previous module, simultaneous (non-concatenative) morphology is very common in sign languages: different morphemes are placed over each other simultaneously rather than being strung together in a linear order (Aronoff et al., 2005).

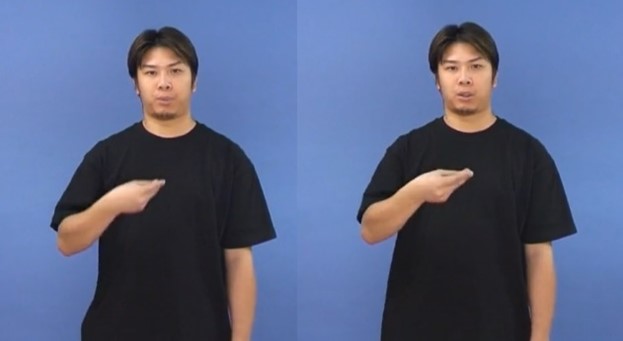

The verb agreement we discussed in Module 9 and 12 is an example of simultaneous inflectional morphology. In Example 1a, the citation form (i.e., the simplest, original form that can be listed in a dictionary) of GIVE consists of a single morpheme. In Example 1b, the morphemes that indicate the subject (at location ‘a’) and indirect object (at location ‘b’) are realized as movement and location modifications overlaid on the citation form (aGIVEb).[1]

Example 1a. GIVE (citation form)

Example 1b. aGIVEb

____________

1 It is uncontroversial that aGIVEb in Example 1b consists of multiple morphemes. However, whether the movement and location modification are comparable to verb agreement in spoken languages is a longstanding debate in the literature. See Mathur & Rathmann (2012) for an overview of the controversies.

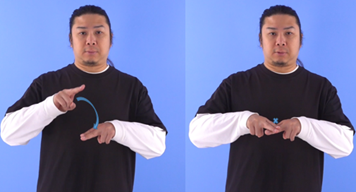

Another type of simultaneous morphology in sign languages is the inflectional modifications that mark temporal aspects. For example, the continuative morpheme can be overlaid on a verb to show that the event lasts for a prolonged period of time without any interruptions (Rathmann, 2005)(Example 2b and 2c):

Example 2a. LOOK-AT (citation form)

Example 2b. LOOK-AT + continuative

Example 2c.

PICTURE CL[=picture on wall], WOMAN LOOK-AT + continuative

‘The woman is looking at the picture on the wall for a long time.’

The continuative morpheme is a bound morpheme as it cannot appear on its own. It alters the movement of the verb root, lengthening its duration.

The habitual morpheme is another temporal aspectual marker. It indicates a general characteristic of an individual. This bound morpheme is expressed through quick and short repetitions of the verb movement.

Example 3a. READ (citation form)

Example 3b. READ + habitual

Example 3c.

IX-1 YOUNGER-BROTHER READ + habitual ALWAYS

‘My younger brother reads a lot.’

The examples discussed so far are all inflectional morphemes as they do not change the meaning and grammatical category of the verbs.

Some derivational morphemes in sign languages are simultaneous in nature as well. In what follows, we will briefly describe two types of derivational morphology: noun-verb distinction and numeral incorporation.

Supalla and Newport (1978) examined a class of nouns and verbs that are semantically and formationally related in ASL. They found that the verbs are usually signed with a longer single movement, while the noun counterparts involve reduplications with shorter and more restrained movements. Below are two pairs of related nouns and verbs from ASL.

Example 4a: SIT (ASL)

Example 4b: CHAIR (ASL)

Example 5a: FLY-BY-PLANE (ASL)

Example 5b: AIRPLANE (ASL)

Supalla and Newport (1978) argue that these nouns and verbs are derived from the same abstract form via two different morphological rules.

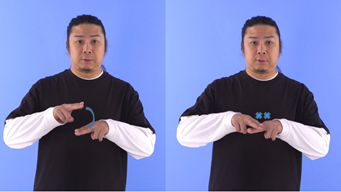

The same derivational distinction between nouns and verbs has been reported in some other sign languages, too. In HKSL, a large number of related noun-verb pairs also show this systematic derivational contrast.

Example 6a: PUT-ON-SHOE (HKSL, verb)

Example 6b: SHOE (HKSL, noun)

Example 7a: OPEN-DOOR (HKSL, verb, B-hand)

Example 7b: DOOR (HKSL, noun)

Numeral incorporation is another common derivational process in sign languages (Fuentes et al., 2010). Example 8a, 8b, 8c and 8d show the HKSL signs for MONDAY, TUESDAY, WEDNESDAY, and THURSDAY respectively.

Example 8a: MONDAY

Example 8b: TUESDAY

Example 8c: WEDNESDAY

Example 8d: THURSDAY

In these HKSL examples, the base sign for DAY-OF-THE-WEEK consists of the parameters of location, movement and orientation. The handshape is unspecified. This base sign can incorporate a numeral handshape to indicate a specific day of the week. In HKSL, quite a number of concepts related to time and number are represented by signs with numeral incorporation. Further examples include grade levels in primary school education, number of months and weeks:

Example 9a: GRADE-ONE

Example 9b: GRADE-TWO

Example 9c: GRADE-THREE

Example 9d: GRADE-FOUR

Example 10a: ONE-MONTH

Example 10b: TWO-MONTHS

Example 10c: THREE-MONTHS

Example 10d: FOUR-MONTHS

Example 11a: ONE-WEEK

Example 11b: TWO-WEEKS

Example 11c: THREE-WEEKS

Example 11d: FOUR-WEEKS

In this module we have introduced a few simultaneous morphological processes. Simultaneity is in fact a prominent feature of sign language grammar. In the next few modules, we will introduce other aspects of sign language grammar which also involve simultaneously organized structures.

References:

- Aronoff, Mark, Irit Meir & Wendy Sandler. 2005. The paradox of sign language morphology. Language (Baltim), 81(2): 301-344.

- Fuentes, Mariana, María Ignacia Massone, María del Pilar Fernández-Viader & Alejandro Makotrinsky. 2010. Numeral-Incorporating Roots in Numeral Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Two Sign Languages. Sign Language Studies 11(1). 55–75.

- Mathur, Gaurav, Christian Rathmann. 2012. Verb agreement. In Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach & Bencie Woll (eds.) Sign Language: An International Handbook. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. pp.136-157.

- Rathmann, Christian, 2005. Event structure in American Sign Language. PhD, University of Texas at Austin, USA.

- Supalla, T., & Newport, E. 1978. “How many seats in a chair? The derivation of nouns and verbs in American Sign Language.” In P. Siple (Ed.), Understanding Language through Sign Language Research. Academic Press.

![]()