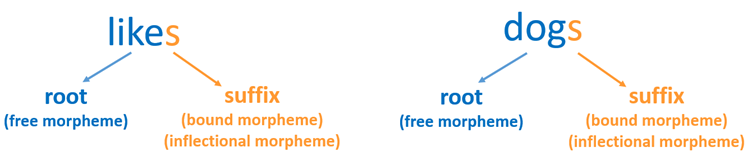

Morphology is the branch of linguistics that focuses on words, their internal structure, and how they are formed (Aronoff & Fudeman, 2005). One of the key concepts in morphology is ‘morpheme’, which stands for the smallest unit in a language that carries a meaning or performs a grammatical function. In the English sentence John likes dogs, the two words likes and dogs each consist of two morphemes:

(1) John likes dogs

Like is a verb, and -s is a morpheme that shows agreement, with the third person singular subject John. –s is a suffix attached after the root like. On the other hand, dog is a noun. The -s that follows it indicates plurality, i.e., more than one, dogs in general. Dog is the root, to which the suffix –s is attached. Like and dog are free morphemes as they can appear on their own. In contrast, the two –s must be attached to other morphemes and can never appear on their own. They are bound morphemes.

The two suffixes perform mainly a grammatical function (i.e., –s for 3rd person agreement and –s for plurality) and do not change the meaning and grammatical category of the roots (likes remains a verb, and dogs remains a noun). Morphemes like these are known as inflectional morphemes. The inflectional morpheme ‘s’ after the verb ‘like’ is a present tense marker.

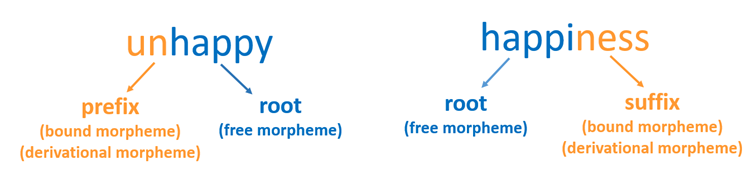

Some affixes change the meaning and/or the grammatical category of the roots, and they are known as derivational morphemes. Take the English adjective happy as an example. When the prefix un- is attached before happy, the meaning of the word is reversed. When happy is followed by the suffix –ness, it becomes a noun. Both un- and –ness are derivational.

English has a fairly large number of prefixes and suffixes in its morphological system. Below are some other examples.

- Derivational morphemes in English:

- non-, im-, ir-, il-, in-, mal-, dis- (prefixes)

- -tion, -ity, -ive, -ly, -ize, -able (suffixes)

- non-, im-, ir-, il-, in-, mal-, dis- (prefixes)

- -tion, -ity, -ive, -ly, -ize, -able (suffixes)

- Inflectional morphemes in English:

- -ed (past tense), -ing (present participle), -en (past participle), -er (comparative), -est (superlative)

- -ed (past tense), -ing (present participle), -en (past participle), -er (comparative), -est (superlative)

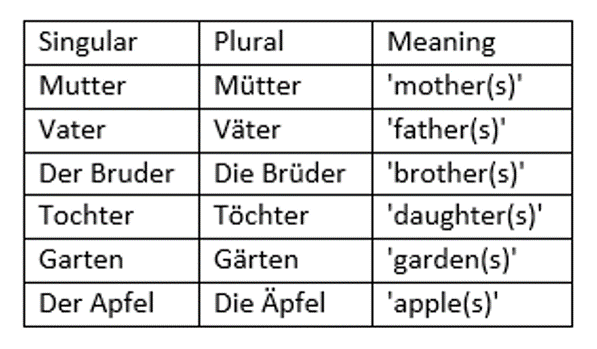

In the above English examples, the inflectional and derivational morphemes are attached either before (i.e., prefixes) or after (i.e., suffixes) the roots. The morphemes are arranged sequentially. In fact, most of the morphological processes in spoken languages are sequential (i.e., concatenative) in nature, as the morphemes are ordered one after another. Non-sequential (i.e., non-concatenative) morphological processes exist in spoken languages, but they are fewer in number. In German, for instance, plurality can be marked by adding an umlaut to the vowel (i.e., fronting an original back vowel, represented by two dots above the vowel), instead of adding a separate morpheme sequentially to the words:

What about sign languages? Which type of morphology is more common? Sequential (i.e., concatenative) or non-sequential (i.e., non-concatenative)?

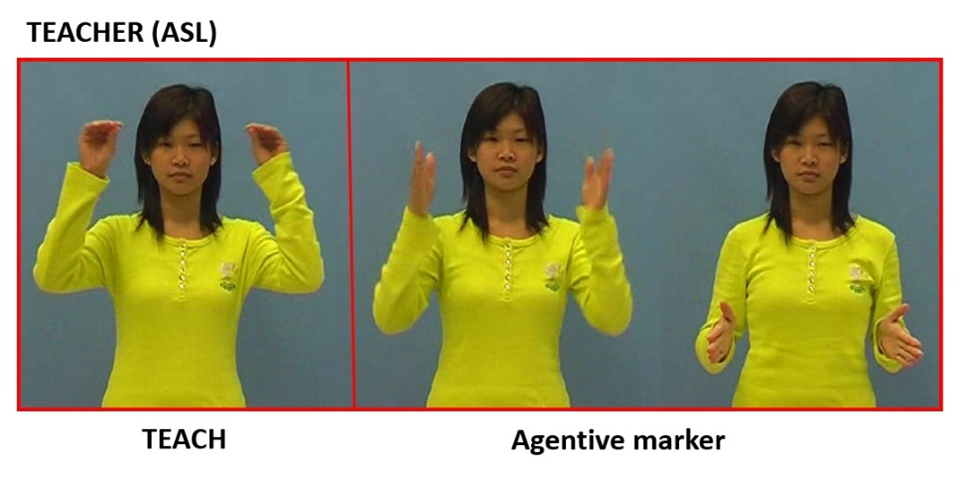

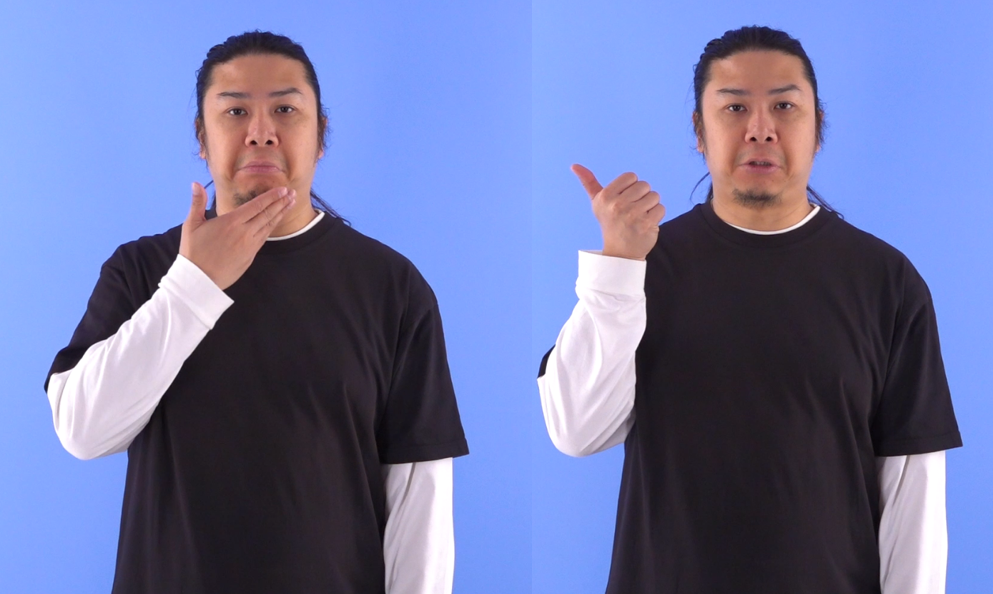

Across sign languages, non-sequential (i.e., non-concatenative) morphology is actually more common (Aronoff et al., 2005). There are some sequential affixations, but they are not common. American Sign Language, for example, has an agentive marker which turns a verb into a noun to stand for a person who does that action. It is a suffix (Sandler & Lillo-Martin, 2006).

Note that the ASL agentive marker is not a direct translation of –er in English. In English, the suffix that is used in student is –ent instead of –er.

The comparative and superlative markers are two other examples of suffixes in ASL (Sandler & Lillo-Martin, 2006)

a. GOOD (ASL)

b. GOOD + ER ‘better'(ASL)

c. GOOD + EST ‘best’ (ASL)

Unlike spoken languages, prefixes and suffixes are relatively rare across sign languages. Sign languages, as visual-gestural languages, favor non-sequential morphology, which involves simultaneous layering of the morphemes. We will discuss examples of simultaneous morphology in sign languages in more details in the next module.

References:

- Aronoff, Mark, Irit Meir & Wendy Sandler. 2005. The paradox of sign language morphology. Language (Baltim), 81(2): 301-344.

- Aronoff, Mark, Kristen Fudeman. 2005. What is Morphology? Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Sandler, Wendy; Lillo-Martin, Diane. 2006. Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge University Press.

![]()